Genealogies of modern atheism are unhelpful to the extent that they present our current religious moment as a fait accompli. Whether one pins the blame on Duns Scotus, the Protestant Reformation, or imperialist capitalism, we instinctively seek the cause of contemporary unbelief in the unchangeable past. While such a procedure is neither illegitimate nor fruitless, we ought also to consider whether any present cultural practices dispose us toward disbelief without our knowing. I propose that our smartphones have become precisely one of those cultural practices.

In his recent book on the Trinity, Fr. Thomas Joseph White, O.P. claims that, while St. Thomas Aquinas is known for his philosophical demonstrations of God’s existence, he “also mentions ways that ordinary human existence (in both our internal and external experience) confronts us with a sense of the transcendent mystery of God.”1 Fr. White calls these “pre-philosophical dispositions of the human spirit” toward belief in God; that is, inclinations of the human intellect and will toward God conditioned by ordinary experience of the world. 2

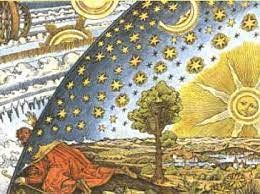

Fr. White calls the first of these, “the experience of order in the world.”3 In his Commentary on the Apostles Creed, Aquinas writes, “No one is so foolish as to deny that all nature, which operates with a certain definite time and order, is subject to the rule and foresight and an orderly arrangement of someone. We see how the sun, the moon, and the stars, and all natural things follow a determined course, which would be impossible if they were merely products of chance.”4 The experience of purpose, harmony, arrangement, and order in the world disposes one to believe that God exists. Such an experience of this order is not philosophically demonstrative of God’s existence, but rather inclines the spirit through the experience to assent to the truth of God’s being.

From the start, we must clarify what Aquinas means by “order.” We often consider order as synonymous with complexity, intricacy, and structural nuance. Therefore, we read Thomas as if he is saying that the elaborate sophistication of the natural world speaks in itself to the existence of the divine. However, for Aquinas, it is not the complexity or intricacy of nature as such which leads the mind disposes to believe in God; rather, it is the particular order of this concrete world as God has created it that inclines our hearts toward Him. Order for Aquinas has everything to do with telos—end, perfection, and fulfillment. God made all things, and, in Christ, is “reconcil[ing] all things unto himself.”5 All things insofar as they exist have some kind of order. But creation as a whole points upward toward God not because it simply is ordered, but because, in creating all things, God ordered creation to manifest his existence.

This distinction between order as such and the divine ordering of reality is important for understanding the potential deception of the smartphone. Our smartphones stand between us and reality and serve as a lens through which we see it. It is increasingly through the interpretive medium of the smartphone that we interact, learn, navigate, discover, understand, and judge. The smartphone appears to manifest the world before our eyes to a degree that ordinary human perception cannot. Yet, while the smartphone does, to an astonishing degree, communicate the content of the world beyond our natural capacities, the ordering of that content is diametrically opposed to the intrinsic metaphysical order of creation. Why? Because while the cosmos in itself is ordered toward God, the cosmos as communicated through the smartphone is ordered toward the consumer, the subject—you.

God creates all things from his own goodness; that is, classically, his own self-love. Therefore, all things arrive at their final end when they are pleasing to God in a way proportionate to their nature. The smartphone forfeits this end to instead render all reality as a sacrifice to the user, with the final end not of being pleasing to God, but to the you and me. To perceive the world as ordered toward oneself—a view transmitted unconsciously to those who habitually view reality through their phones—is to dive headlong into the capital vice of Pride. Pride is to embrace a perception of reality in which the fulfillment and perfection of all things is found in their service to your pleasure. And pride is the preeminent cause for rejecting the existence of God.

Fr. White describes the second disposition as “the basic human experience of time, finitude, and contingency.”6 Fr. White locates this in Aquinas’ Commentary on John, where Aquinas, describing the way that ancient peoples came to believe in God, writes:

They saw that whatever was in things was changeable, and that the more noble something is in the grades of being, so much the less it has of mutability... We can clearly conclude from this that the first principle of all things, which is supreme and more noble, is changeless and eternal.7

As Fr. White explains, the experience of time, finitude, and contingency, “naturally raises the question of remains eternally, or of what lasts, behind or underneath all that changes.”8 Humans intuitively recognize that contingent, finite realities cannot provide ultimate explanations for why they exist and for what they most deeply and truly are. The existential impetus of such an experience grows exponentially when we then realize it applies also to ourselves. We are finite and contingent. Our powers, knowledge, and being are limited, and these limitations always serve as a reminder that one day we shall die.

But the smartphone clouds this awareness of our own finitude and contingency by giving us the illusion of limitless power and substitute eternal existence. Do you desire to know any information which humankind has gathered and organized since the advent of literacy? Your smartphone can fulfill this desire with god-like efficiency. Do you desire to translate your presence virtually to any place on the earth? Facetime, text email, and social media accomplish this with ease. Do you desire any imaginable gratification of your animal appetites instantaneously? Your smartphone renders the spoils without judgment or question

Not only does the smartphone extend human powers immensely, but it also seems to offer a dimension of quasi-eternity. Consider, for example: can one ever scroll to the bottom of Facebook? Can one plumb to the terminal depths of Instagram? Can one traverse and survey the far reaches of Youtube? Can anyone set out to measure the outer boundaries of the Internet? These rhetorical questions bear out the same answer. When one steps into the limitless phantom reality readily at hand in the smartphone, one turns away from that daily experience of finitude and contingency which turns our eyes upward to the truly eternal, and wander instead in the false image of the everlasting offered therein. The smartphone gives us the illusion of limitless power and eternal existence, but in fact becomes an obstacle to the actual attainment of these good things in the way God wishes to give them. It is no accident that we are perennially incapable of recognizing how long we have spent on our devices, for they are manipulated by our Enemy to emulate that Realm which stands above time itself.

Finally, Fr White describes the third and fourth pre-philosophical dispositions toward belief in God as the parallel and inextricable human desires for happiness and for truth.9 For Aquinas, all persons, simply by encountering created realities, desire to possess them insofar as they are good; that is insofar as having these realities will make them happy. Similarly, persons desire ineradicably to move intellectually from the fact that certain realities exist, to the deep knowledge of what these realities are. These are in a sense the same desire. For Aquinas, to know a thing is to possess it in the most intimate way possible. As Josef Pieper states it, “To know is by the nature of knowing to have; there is no form of having in which the object is more intensely grasped.” 10Humans desire to possess, to have, to own the things which are good and the deepest way to possess these good things is to know them in their essence. Therefore, since humans cannot help but desire happiness through knowledge, and because their desire for these happiness through knowledge will never be satisfied by the obtaining and knowing of created realities, they are led spiritually upward to the belief that there must be something transcendent which is the True Object of our hunger for happiness and truth.

Our smartphones dull our experiences of this hunger for happiness and truth through the cultivation of the sin of curiosity. For Aquinas, curiosity is a sin because it is the search for knowledge, not for the sake of ultimate happiness, but rather because “one takes pride in knowing the truth…or because one uses the knowledge in order to sin.” One of the ways we cultivate curiosity is, “when a man desires to know the truth about creatures, without referring his knowledge to its due end the knowledge of God.”11 It is apparent how this relates to the first point. Insofar as we perceive reality through our phones as ordered toward ourselves and toward the fulfillment of our own desires, our desire becomes disordered the moment it emerges. All pursuit of knowledge through the instrument of the smartphone becomes perniciously inclined by its very form to the vice of curiosity, at least potentially. Even the most cursory critical glance at our smartphone use clearly displays that we look on the luminous sanctum of our glowing screens not so that we might grow in knowledge of God, but because we take carnal pleasure in the act of looking itself. Our innate desire for happiness and truth is dulled, in the words of St. Augustine, “not because [we are] replete with it, but the emptier [we are], the more unappetizing such food [becomes].”12

Human persons are disposed toward a belief in God ordinarily through the experience of order in the world, of their own contingency and finitude, and of their ineradicable but unsatisfied desire for happiness through truth. These experiences pre-philosophically incline the human mind and will to assent to the claim that God exists. Yet, these experiences do not have the same effect on modern man that they have had on his ancestors, primarily he has invented for himself an existential cocoon: the smartphone. Christians are not safe from such deceptions because of their supernatural faith, for grace builds upon and elevates nature, but does not supersede or destroy it. We ought to judge prudently what actions follow these considerations on the danger of the smartphone. Can we seriously continue our current uncritical smartphone practices if the danger is nothing less than infinite in scope?

Thomas Joseph White The Trinity: On the Nature and Mystery of the One God (Washington D.C: Catholic University of America Press, 2022), 22.

Ibid.

Ibid, 23.

Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Apostles Creed, trans. Joseph B. Collins (New York, 1939), https://isidore.co/aquinas/english/Creed.htm

Col. 1:20

White, The Trinity, 23.

Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on John trans. James A. Weisheipl, O.P. and Fabian Larcher, O.P (New York: Magi Books, 1998) https://isidore.co/aquinas/english/SSJohn.htm

White, The Trinity, 23.

Ibid, 23-24.

Josef Pieper, Happiness and Contemplation, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 1998), 65.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica II-II.167.1, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (Benzinger Brothers, 1947) https://isidore.co/aquinas/summa/SS/SS167.html#SSQ167OUTP1

Augustine, Confessions, trans. Henry Chadwick (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 35.