In his treatise on faith in the Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Aquinas asks the question, “Does having reasons for what we believe decrease the merit of our faith?”

He answers, of course, in the negative. However, he makes an illuminating and provocative analogy near the end of his discussion of that question that deserves special attention. He writes:

Whatever is in opposition to faith, whether it consists in a man's thoughts, or in outward persecution, increases the merit of faith, in so far as the will is shown to be more prompt and firm in believing. Hence the martyrs had more merit of faith, through not renouncing faith on account of persecution; and even the wise have greater merit of faith, through not renouncing their faith on account of the reasons brought forward by philosophers or heretics in opposition to faith.1

The first part of Thomas’ argument finds its roots in the earliest experience of the Church. Martyrs, on account of the suffering they endure for the sake of Christ’s name, receive God’s favor and a share in his life in a higher, more glorious way.

Why else would St. Ignatius of Antioch beg the Romans not to interfere with his martyrdom with the following almost unimaginable urgency:

Allow me to become food for the wild beasts, through whose instrumentality it will be granted me to attain to God…Rather entice the wild beasts, that they may become my tomb, and may leave nothing of my body; so that when I have fallen asleep [in death], I may be no trouble to any one. Then shall I truly be a disciple of Christ, when the world shall not see so much as my body.”2

Furthermore, in Dante’s Paradisio, it is only with the appearance of the martyrs in the fifth sphere of Heaven that Christ and his Cross are first seen, and that Dante’s “soul was so enraptured by those strains / of purest song, that nothing until then / had bound my being to it in such sweet strains”-- not even Beatrice.3

However, the second part of Thomas’ claim that is novel; namely, that “the wise” receive a reward analogous to the martyr’s reward to the extent that they resist the “reasons of the philosophers and the heretics in opposition to the faith.” Dante seemingly holds the same view, though in an implicit and imagistic way, for it is directly from the presence of Sts. Bonaventure and Thomas Aquinas himself that Beatrice leads the poet upward to the vision of the martyrs.

Thomas is claiming that, to the extent that the wise experience the intellectual violence of compelling arguments against the Christian faith and yet steadfastly assent to the truth of that faith, they are like the martyrs, who, despite the compulsion of physical violence, stand firm in their love of Christ.

Yet the possibility of such a magnificent exaltation for both the wise man and the martyr carries with it equal dangers.

For example, in the early centuries of the Church when she was persecuted by the Roman Empire, there was a practice of “self-reporting,” of Christians turning themselves in to the Roman government that they might lay hold the glory of martyrdom voluntarily and with certainty. On its surface, such a practice seems to manifest almost superhuman fortitude, a thumotic act of defiance in the face of the Church’s enemies.

However, church authorities forbid such a practice consistently, for, as Josef Pieper puts it in The Four Cardinal Virtues, “the Fathers of the ancient Church, from St. Cyprian to St. Gregory of Nazianzus and St. Ambrose, actually assumed that God would most readily withdraw the strength of endurance from those who, arrogantly trusting their own resolve, thrust themselves into martyrdom.”4 What at first appears to be brazen heroism shows itself, when stripped of divine assistance, to be vanity and cowardice.

We can understand the Fathers’ thinking if we look more closely at the spiritual anatomy of “self-reporting.” The act of presenting oneself to the authorities for martyrdom is either an act of pridefully trusting in one’s own ability to endure martyrdom faithfully (and thereby an act of false Pelagian self-confidence) or an act of presuming God’s grace in the hour of trial (and thereby an act of what the Scriptures call “putting the Lord your God to the test”). Either way, the sin is great, for either one claims that the kingdom of Heaven can be claimed by natural abilities alone, or that the grace of God can be predicted, manipulated, and executed at will. Those who presume to grasp martyrdom on their own terms will find themselves unequal to the task, and they will instead condemn themselves further through the public denial of their Lord.

As the trials and rewards are similar for the wise man and for the martyr, so too are the inherent dangers. As the Christian who intentionally seeks out martyrdom from presumption or pride will fail to endure, so too the self-appointed defender of the faith, the modern Father Ferapont, who sees gnostics, communists, liberals, conspirators, and the like hiding in every corner and rises to cast them out for all, may find the philosophies, heresies, ideologies, and myths mightier than he anticipated, and may make a public mockery of the faith he stepped forth to protect.

Examples of this vice abound in the age of the internet. But, if the vice exists—and I think to say that it exists conspicuously is all but above dispute—the virtue must also exist, and must be in some way intelligible. If it is possible to open oneself up to the violence of the “wisdom of this world” in an illegitimate, pernicious way, what constitutes a legitimate, courageous suffering of the world’s most clever contrivances? Who among us is called by God to, “[Cast] down imaginations, and every high thing that exalteth itself against the knowledge of God, and [bring] into captivity every thought to the obedience of Christ”?5

The call to martyrdom is attended by clear signs. To be arrested, brought before Caesar, and thrown before the lions—such is the clear imperative to follow Christ unto death. But the call to intellectual suffering is often more difficult to discern.

The Eastern Fathers of the Church were sensitive to the theological hubris described above and took pains to justify the books they wrote. A typical example is in the opening chapters of St. Maximus the Confessor’s On the Ecclesiastical Mystagogy.

You once listened to me relating in a cursory and summary fashion—such as it was—the contemplations of another esteemed elder, who is truly wise in divine things…Since the contemplations were beautiful and mystical and, above all, valuable for teaching, you pleaded with me to draft for you a written exposition…But at first ‘the reason I was reluctant, for—I will speak the truth’--I declined your proposal, beloved reader, was not because I did not wish to give you my thoughts in any way to the best of my ability, but because I have not partaken of the grace that leads those who are worthy into such an undertaking…Nevertheless, at last yielding to the compulsion of love, which is stronger than all, I accepted your demand willingly. 6

Notice the parts of Maximus’ justification: knowledge, even if derivative or imperfect (“relating in a cursory or summary fashion…the contemplations of another elder”), external compulsion (“pleaded with me to draft for you a written exposition), self-understanding (“I have not partaken of the grace that leads those…”), and love for the intended reader (“yielding to the compulsion of love, which is stronger than all”).

The intellectual martyrdom of defending the faith is justified when the “wise” are knowledgeable, humble, moved by the specific need of the moment, and motivated by love for those who will receive his written words.

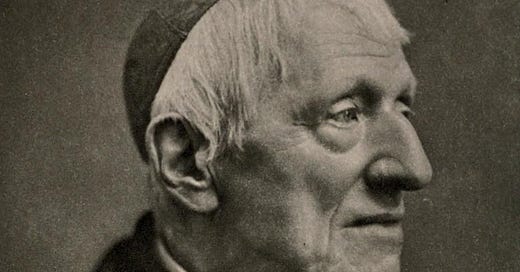

In shorthand, this is what we call: The Newman Condition.

St. John Henry Newman was an English priest, philosopher, polemicist, poet, and novelist whose life spanned most of the 19th century. His breadth and brilliance are often reduced and read through his conversion from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism in 1845, and his story is simplified and utilized to garner converts. However, here, we seek to understand and imitate Newman as an intellectual martyr—that is, one who deeply suffered beneath the force and violence of the philosophies which haunted his day, and responded exemplarily to the specific needs of his time with wisdom, humility, and love.

Our present task, as lesser lights, is to live and speak as he lived and spoke, not from a sense of worth or particular ability, but from the need of the present day. The hour is late; the day is far spent. It is no time for men of inferior gifts to excuse themselves on account of their underwhelming talents. For, as St. John Henry Newman writes:

Surely, there is at this day a confederacy of evil, marshaling its hosts from all parts of the world, organizing itself, taking its measures, enclosing the Church of Christ as in a net, and preparing the way for a general Apostasy from it…this Apostasy, and all its tokens and instruments, are of the Evil One, and savour of death. Far be it from any of us to be of those simple ones who are taken in that snare which is circling around us! Far be it from us to be seduced with the fair promises in which Satan is sure to hide his poison! Do you think he is so unskilful in his craft, as to ask you openly and plainly to join him in his warfare against the Truth? No; he offers you baits to tempt you. He promises you civil liberty; he promises you equality; he promises you trade and wealth; he promises you a remission of taxes; he promises you reform. This is the way in which he conceals from you the kind of work to which he is putting you; he tempts you to rail against your rulers and superiors; he does so himself, and induces you to imitate him; or he promises you illumination—he offers you knowledge, science, philosophy, enlargement of mind. He scoffs at times gone by; he scoffs at every institution which reveres them. He prompts you what to say, and then listens to you, and praises you, and encourages you. He bids you mount aloft. He shows you how to become as gods. Then he laughs and jokes with you, and gets intimate with you; he takes your hand, and gets his fingers between yours, and grasps them, and then you are his.7

St. John Henry Newman, pray for us.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica II-II.2.10, https://www.newadvent.org/summa/3002.htm

Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Romans 4, https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0107.htm

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, trans. John Ciardi (New York: New American Library, 2003), 717.

Josef Pieper, The Four Cardinal Virtues (Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), 118-119.

2 Corinthians 10:5

Maximus the Confessor, Ecclesiastical Mystagogy, trans. Jonathan Armstrong (Yonkers: SVS Press, 2019), 46-47.

John Henry Newman, “The Times of Antichrist” in The Patristical Idea of Antichrist, https://www.newmanreader.org/works/arguments/antichrist/lecture1.html