Simple, obvious truths always evade comprehensive definition. Scientists speculate confidently on the remote, celestial cataclysm which sired the universe, but find their tongues curiously tied before the question of why we sleep. The philosopher, serene and articulate on the nature of the cosmos, finds himself stuttering and disturbed by the nature of his mother-in-law.

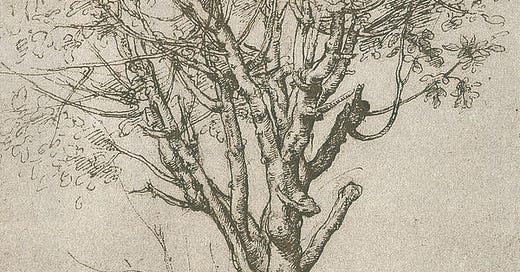

Such commonplaces tend to elicit two very different responses: complacency and neurosis. Some blissful, inattentive men skim heedlessly over the givenness of reality. Others, usually out of touch with community and therefore reality, fixate with equal parts ingenuity and mania on reducing, dividing, and rationalizing that which is basic, integral, and self-evident. The former occurs when men ignore the glory of great, old trees; the latter is an abbreviated history of modern epistemology.

Trees and human knowledge present especially interesting examples. In the ironic, paradoxical mirth of divine providence, knowledge, though within man’s mind, stands beyond his understanding. Despite this, he does not cease from the frantic construction of myriad grand systems elaborating what knowledge is and how it works. Inversely, the tree, with almost forceful antipathy, sways and blossoms quite outside and apart from man’s head. Yet the tree causes none of the sweaty vexation previously described, for, though content to flourish and shade without man, it finds ready ground within him—that is, within his intellect. Such fundamental compatibility, like lovers in a comedy, means man will turn his attention entirely in other directions.

Regardless of their apparent antitheses, the tree is a prime, if often forgotten, metaphor for human cognition. We speak of “branches of knowledge” and “the root of the matter.” Trees reach heavenward, growing by fits and starts up toward the sun, the classic symbol of the Good and the True. Birds, another poignant image of man’s immaterial element, nest in the tops of trees, indicating that higher contemplation in which the mind rests. Finally, it is perhaps no accident that the tree has become the foremost vehicle by which man shares his knowledge, i.e. through paper.

The natural relation between the tree and human knowledge participates in the higher, supernatural mystery of faith. Man falls by the tree of the knowledge of good and evil; he is saved by gazing on the Cross, the tree of life made new. Our Lord himself was not only a revelation of Knowledge, but also a craftsman of the Tree.

Much more could be said concerning the way trees illuminate the theological virtue of faith. At present, however, I am concerned with how the image of the tree is also an image of tradition, a lens by which to see the role of tradition in the faith. St. John Henry Newman has given this connection supreme articulation. In short, Newman illustrates the development of Catholic dogma through the metaphor of biological maturation. As the whole tree is present in the seed but must pass through necessary transitional forms on the way to full flourishing, so through the tradition of the Church is the whole deposit of faith made explicit.

On the one hand, the illustration is descriptive. The corpus of dogma which the Roman Catholic Church declares to be revealed by God has not in all times and places been pronounced with equal certainty and precision. For the Church, this is only historical fact, and it has little to do with the truth of that dogma. The assurance about faith and morals the Church professes does not stem from the authority of historical research, but from Christ’s promises, especially to the successor of St. Peter. The development of doctrine is primarily apophatic, an explanation which reconciles history with divinely revealed truth. It is important to realize that it does not ground that truth in the explanation. Reconciliation between apparent contradiction and actual harmony has always been the central service which history, science, and philosophy give theology, never demonstration or proof. Tradition is an indispensable element in this apologetic, for it is the instrument of this reconciliation.

On the other hand, the notion of development marries two basic Catholic ideas which appear to be in tension. The Church insists both that Christ handed to her the complete deposit of the faith in the twelve apostles and that she does not yet possess this grace of faith in its highest perfection. In other words, though the Church knows the faith, she does not know it in that fullness which grace is sufficient to impart. While intuitive in the abstract, degrees of knowledge are difficult to conceive concretely. To this end, a return to the image of the tree is illuminating.

One of the peculiar, often unnoticed characteristics of the natural world in general, and of trees in particular, is sheer, spectacular diversity.Trees seem gratuitously varied, both in quantity and quality. One of the common, obvious, but wonderful realities of this world is that foliage appears superfluous in number and kind. However, in sharp contrast with us moderns, nothing is truly superfluous for the ancients and medievals. For them, diversity is what happens in the existential encounter between matter and form.

A few words of propaedeutic explanation are required. In the mainstream tradition of ancient and medieval philosophy, material beings are composed of form and matter. For this tradition, matter is not how we understand it, in terms of protons, neutrons, atoms, and quarks. Even these foundational substrates participate in what our Western forbears call “form.” For them, matter is the undefined, unrealized, delimited principle of potency. Matter is unintelligible, chaotic, and impotent without the principle of form. Form, far beyond simple shape and appearance, is the metaphysical structure of determinate beings, their ontological organization, and the source of their unity, identity, life, and operation.

For the ancients, form was first in importance, for form transcends the individual object in which it subsists. The form of dog is not exhausted by Rover, nor the form of tree by the live oak. In a sense, there is always more in or to the form than could be expressed in a particular existent. Demonstrations abound in experience and theory. As stated before, trees of widely divergent kind are united under the form of tree, yet no individual tree could express all the multivalent distinctions encompassed in the universal “tree.” In other words, no tree can produce all possible fruits, grow all possible bark, or shed all possible leaves. Furthermore, form, being composed with and therefore other than matter, must be immaterial, and consequently intellectual. Form comes forth from mind. From the artisan to the divine, form emerges from a consciousness of sufficient power to shape reality according to set intentions. This intellect exceeds its creation; so too, the form that proceeds from it.

Diversity, then, is the natural fall-out of a form disseminating in the world, the rippling effect of a transcendent idea pressing in upon immanence. Each tree is a distinct but related riff on the same theme, an individual but not independent attempt to express that which stands on the far edge of expression. The form of a tree is of such superabundant beauty and goodness that, to really manifest it, countless surveys into its depth must draw out its innumerable possible incarnations.

Such abundant multiplicity relates the tree again to human knowledge. A great variety of trees is needed to adequately express the form of tree; man needs a great variety of trees to ascend gradually to the knowledge of their form. The two exist as twin sides of a mysterious, divine gift. God desires to give himself to man, for in Him is man’s happiness. One way he chooses to do this is through nature. God creates the natural world after a form which comes forth from and leads back to Himself. Therefore, God expresses this form diversely that a greater portion of its splendor may be shown, and that man may encounter that splendor in a way that draws him up toward his Maker.

Despite the circuity of the path, these considerations bring us finally back to tradition. Just as simple, obvious truths evade easy explanations, but require multiple philosophical excursions; just as transcendent forms can never be expressed and known thoroughly by a single instantiation, but require many, diverse iterations; so also the deposit of the faith cannot be manifested fully or explicitly nor known with certainty without a tradition of attempts to articulate the same ineffable realities set down in the writings and sayings of the apostles.

Repetition of the same truth by Catholics of different times, cultures, and languages is not redundant or simply practical and advantageous, but indispensable. In the same way that Christ’s love is one and the same always, yet transforms the saints in scarcely imaginable, multifarious ways, so Christ’s truth, which is coterminous with his love, finds expression in countless varied but essential voices throughout the Church. If God has revealed Himself to the world, and if it is possible that the world should receive this revelation, then a tradition extending from the ascension of our Lord to the present day exists to express the unfathomable truth of man’s salvation in a way that man can truly know.

I appreciate the zeal, joy, and wonder you embody in developing the analogies which embody the unity and diversity, i.e. the fullness, mystery, and beauty in nature as an expression of the divine.

This calls to mind the other analogy I have heard for tradition. Not only is it a tree, but it is a sculpture. We slowly chip away at the marble to uncover the figure lying within, and so just as we need to repeat the theme over and over again in different places and with different instruments to see the commonalities, so too do we slowly remove things to clarify what the original tradition was all along.